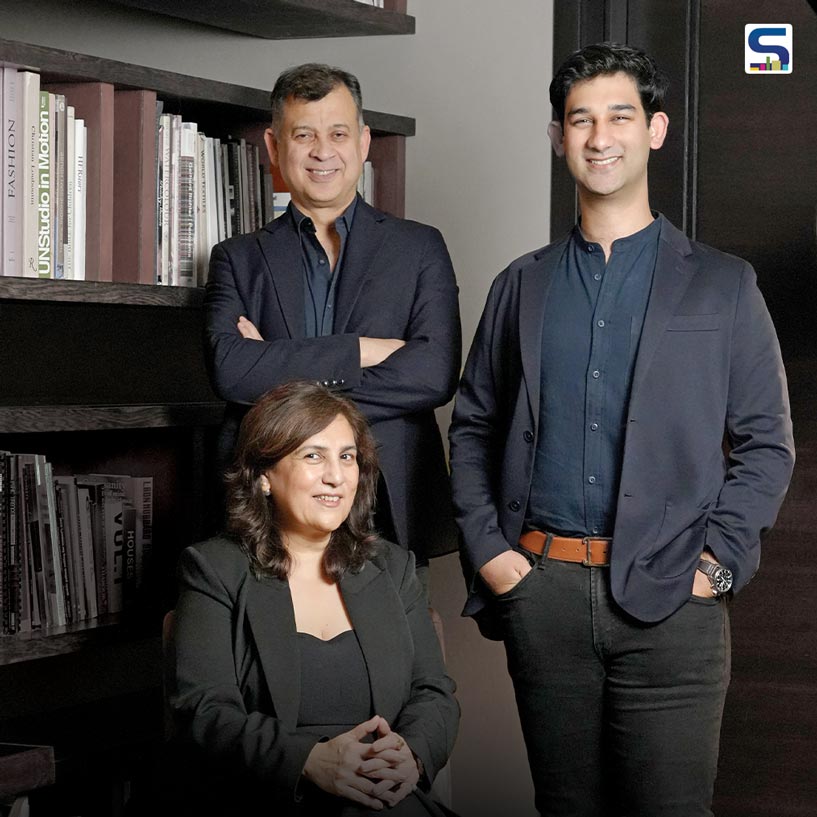

Habitat Architects was founded in 1994 by Zafar Chaudhary, Ranjodh Singh and Monika Choudhary. The firm is renowned for blending traditional architectural methods with modern techniques, showcasing an immersive design philosophy and meticulous attention to detail. The recent addition of their children, particularly Sahir Choudhary as a Senior Architect And Director Of Operations, marks the firm’s evolution and the integration of fresh perspectives. Verticaa Dvivedi, Editor-in-Chief of Surfaces Reporter® (SR), conducts an exclusive conversation with the trio!

Let’s start with when you first met your partner Ranjodh Singh.

Zafar:Well, Ranjodh and I go way back - we were batch mates at Chandigarh College of Architecture, starting in 1987. I met Monika around the same time; we knew of each other since we were neighbors. So, it’s been quite some time—almost four decades now, about 37 or 38 years.

When did you first start exchanging ideas about working together in architecture, maybe starting a firm together?

Zafar: Our firm’s growth has been quite organic. It wasn’t something that happened on a specific day or in a particular year. I and Ranjodh simply started working together on various projects without formally establishing a firm. Over time, as we took on more work and our teams began to grow—initially, it was just the two of us, with Monica occasionally lending a hand—we realized that we had enough work to formally establish the firm. So, it was really born out of our shared passion for working on projects and bringing our ideas to life.

I was an art student from a young age, and I’ve always loved drawing—my schoolbooks were filled with scribbles. Naturally, I gravitated toward being a serious art student, fascinated by the use of colors, textures, and storytelling through art. This foundation in art was invaluable during my time in Architecture College. When I transitioned to working in three dimensions, my artistic expression became immersive. It wasn’t just about observing an object from a distance; it was about standing within it and experiencing it firsthand.

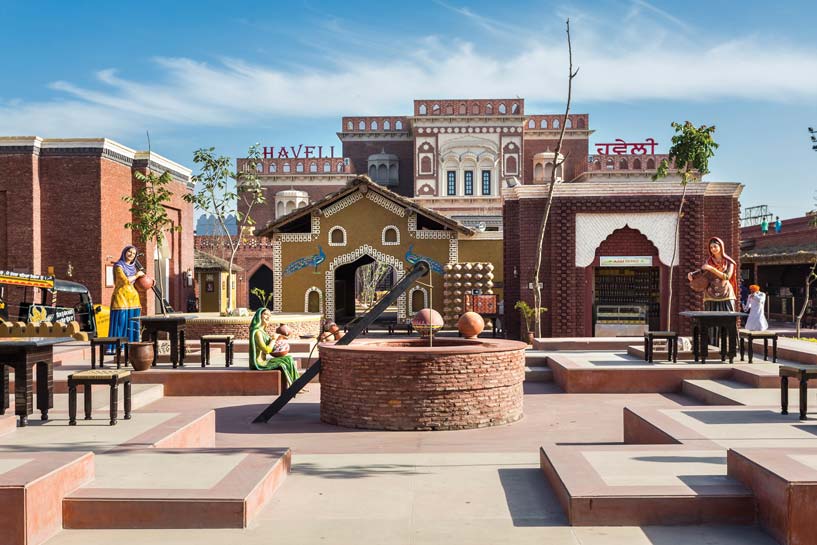

Haveli An ode to the legacy of Punjab

30 years ago, architecture and client perceptions were different, influencing how architectural firms approached projects. How do you view this evolution?

Zafar: Back then, architecture was not well understood, and architects were often referred to as ‘NakshaNafis,’ implying that we were just people who made drawings and did drafting. Our biggest challenge was to shift from this perception to being seen as creators of three-dimensional stories.Initially, architects weren’t regarded as artists but rather as having a basic understanding of construction, which we actually lacked. We learned extensively from craftsmen, bricklayers, masons, carpenters, and other trades people. Those early years were our most crucial period of learning in construction.

I recall many early site visits where we interacted directly with these skilled workers. We spent time with carpenters, observing and sometimes even participating in tasks like chiseling wood or painting walls, which often meant we had to clean up after ourselves the next day. This hands-on experience with craftsmen was invaluable.Without computers or the internet, learning from those who physically built structures was our only way to understand the construction process from the ground up. This practical education became a fundamental part of our firm’s foundation.

Given that knowledge about architecture was limited and communication technology was at its nascent stage, what were your means to communicate design ideas?

Zafar: My skill in sketching played a crucial role in this process. Back then, we used to draw what were called perspectives - essentially 3D renderings - to help clients visualize the design. Since we were new and didn’t have a well-established reputation, it was important to use sketching to convey our ideas clearly.

I would create detailed drawings of a room, showing the flooring, surfaces, ceiling, furniture, and doorways. To make these sketches more relatable, we would physically present materials next to the sketches—like a mood board. This way, clients could see how the materials would look in context with the design. We would buy samples, such as a piece of stone, and place it next to the sketches to give a tangible sense of the design. This hands on approach helped clients align with our vision, though it often took several iterations to get everything right. While today’s world relies heavily on digital renders, we still fondly remember the days of pencils, colored pens, paints, and brushes. Although our tools have evolved, our core process hasn’t changed much. We still believe in aligning with the client’s vision because, ultimately, it’s their space they will inhabit.

As for sketching, yes, I still do it. I begin all my initial design iterations with a sketch. The team then takes over, and while the younger generation often uses computers for sketching, I continue to enjoy the traditional method with paper and colored pens.

You began your journey with Abimanyu Dalal? Please share your experiences with him

Zafar: Working with Abimanyu Dalal was a fantastic experience. It was a fun time, though he might have found me a bit annoying at times! What stood out most was how he approached his role as a teacher first, and an architect second. He really helped us make sense of what we had learned in college -understanding geometry in architecture, proportions, and immersive design.

One of my fondest memories is of the time spent after office hours, where we would sit and chat about everything under the sun. It was during this time that he also assisted with my thesis, which was a massive project on riverfront development in Delhi. I had been struggling with it for six months, but Mr. Dalal helped me see it in a new light and guided me in putting it all together. I learned a tremendous amount from him and have great respect and fond memories of our time working together.

How would you define your design philosophy?

Monika: Our approach has been evolutionary, learning from both small and large projects. What we value most is the lessons we’ve learned and how we apply those insights moving forward. We don’t have one project that defines us; instead, our essence is captured by the concept of ‘Vision meets Detail.’ This means that while we start with a concept or vision, the success of our work comes from how meticulously we detail and execute that vision. The true magic happens when vision and detail align perfectly.

Garden Estate A modern-day interpretation of the classical English garden

Your operational skills, business acumen, and strong design background complement with Zafar’s architectural capabilities, bringing a valuable mix to the table.

Monika: The roles that I play now didn’t come naturally to me—I never even thought about it. We were very content being two artists working together. When we fell in love, got married, and started our lives together, our work, which was our passion, also became our livelihood. As we grew, it became clear that understanding aspects like management, finances, and team building was essential. Scaling up from a studio to an organization, especially for creative people, is challenging because we’re taught to create, not to organize.

Our journey has taught us that what got us to a certain point wouldn’t necessarily take us to the next level. We had to adapt, learn, and multiply our skills. Though I didn’t initially choose to be in the business side of design, it became a necessity. My partner excels in visualizing design and his passion is unparalleled. With children growing up, I found time to focus on the business aspects and educate myself through management classes, both in-person and online. While he upgraded his design skills, I worked on enhancing my management abilities. These milestones have shaped where we are today and how we’ve evolved.

Your firm has been constantly evolving. When was the last turning point and what were are the developments it brought along?

Zafar: When COVID happened, we realized that our way of working needed to change. We didn’t stop working during the pandemic; instead, we sent all desktops and computers to our team members and continued engaging through emails and virtual meetings. This period became a significant milestone for team building and adapting management techniques that went beyond the studio environment and drew from management school principles.

How did you manage to learn and develop your skills while juggling responsibilities at home?

Monika: I always say, women are born managers; it’s like a gift in our DNA. The level of multitasking a woman can achieve often surpasses that of men. When you’re young and choose to get married and have children, you’re already juggling multiple roles. Fortunately, if you’re passionate and have a supportive environment that allows you to flourish creatively, as I did in my family growing up and in my married life, you can thrive in both areas. Management came naturally to me, partly due to my upbringing. My father instilled in me a sense of organization, while design came from my mother and my maternal grandfather, a fashion designer. As I moved into this field, I realized that management is crucial. While you can manage a lot with your own hands, scaling up to involve more people requires different skills. Management teaches you to organize work and people, handle various personalities and environments, and address human reactions. Management is something we both learned and adapted to as needed. Whenever a requirement arose, one of us would step up. Zafar created the need for management by expanding our operations, and I adapted to that need, ensuring that everything ran smoothly.

Can you share some behind-the-scenes stories where things didn’t go as planned? How did your strong collaboration handle those situations?

Zafar: Early in our career, we were tasked with designing a highway restaurant in Punjab. Instead of creating a typical highway stop, we envisioned something unique—a nostalgic art and crafts village reflecting Punjab’s traditional culture. The location was in Jalandhar, an NRI belt, which further inspired us to create an immersive experience. We travelled to various villages, studying traditional architecture, materials, andtechniques, like the use of timber and lime-based flooring. The client was initially skeptical, but supportive of the idea. We transformed the project from a simple restaurant into a placemaking initiative, envisioning it as a vibrant cultural destination. The project became a significant success and is now a renowned example of placemaking in the region. The client embraced the concept, allowing us to innovate freely, which led to the revival of traditional materials and techniques, like the “Lori bricks” used in the construction. The project not only became a landmark but also rejuvenated a traditional brick industry that had almost faded away.

While working on this project, we delved deeply into the architectural history of the region. We noticed that traditional “Nanak bricks,” used in old village buildings, were becoming obsolete. We sourced these bricks from demolished old structures and incorporated them into our design. This choice was not only a nod to heritage but also helped revive a nearly lost industry. Our work inspired others to use these bricks, turning them into a fashionable material. The (HAVELI EXPRESS) project evolved into a dynamic, culturally rich destination, and the once-fading brick industry experienced a revival. This has been a particularly rewarding aspect of our work, knowing that our efforts have had a lasting impact.

Nazcaa A restaurant in Dubai inspired by the Nazca Lines of the Peruvian desert

Any recent challenges that your firm faced and how did you manoeuvre through it?

Zafar:We faced a significant challenge during Covid for a project in Delhi when we had to manage everything remotely.The client, project management team, and suppliers were all working from home, and we needed to build and finalize the project entirely in a digital format before any physical work could begin.With restrictions delaying the groundwork by six months, we had to handle everything—materials, details, and design—completely online.One of the biggest challenges was managing all aspects of the project without physical samples. We designed and built everything in 3D, finalizing all details and materials digitally before any work began. This was a huge learning experience for us in terms of digital management and design, particularly with fabrics, textures, and colors. It really highlighted how crucial digital skills and material expertise are in today’s project management landscape.

Monika: So, Zafar has an incredible photographic memory—he can recall 500 names and colors and relate them to digital representations, even if they don’t look exactly right on screen. His ability to remember the specific details, like a particular shade of paint or a unique fabric, ensures that the final product matches his vision perfectly. It’s something I deeply admire, as I, being a designer myself, sometimes find it challenging without the physical touch and feel. This experience really introduced us to the world of digital technology and management. I also want to give credit to our children during the COVID times—they played a huge role in advancing our technological capabilities. Each screen shows colors differently; a Samsung looks different from a Sony or an Apple. This made us realize the importance of physical touch and accurate color representation. Our kids helped us navigate these challenges, teaching us a lot along the way. It’s been a journey of learning and teaching, where the children have both learned from us and taught us in return.

What about your children - how old are they, and what are they up to?

Monika: We have two children, a son and a daughter, who are like twins—just a year and three months apart. Both are architects with distinct yet complementary personalities. Our son, Sahir, is a profound and intelligent individual with a keen interest in technology and design. His background in mathematics, history, art, and physics has shaped him into someone who merges creativity with technical expertise. He’s introduced virtual and augmented reality to our practice and now serves as our Chief Operating Officer, leadingoperations and urban design. Our daughter is equally talented but brings a different energy. She’s known for her vibrant creativity and strong sense of color and design, evident from a young age. She’s always had a knack for appreciating fine details, whether in fashion or architecture. Her energy and social skills bring a dynamic presence to our team. During COVID, having both children working with us was a transformative experience. It reinforced the magic that happens when we all put our energy into something together. Although they initially planned to gain experience elsewhere, they have since decided to join us permanently. Their return has been a welcome and encouraging development for our firm.

Are there any key lesson you’d like to share with this generation?

Zafar:The biggest lesson I’ve learned in my career is the importance of patience. It’s not something I’ve always had, but it’s become a defining characteristic for me. Patience helps you approach things more thoughtfully and allows ideas to develop properly. You need to be patient with the process, with stakeholders, and in building something from the ground up. It’s not about instant gratification but about steady, thoughtful progress. Beyond the design aspect, which varies for everyone, this human trait of patience, self-belief, and trust in the process is crucial. If you stay patient and believe in your vision, things will eventually manifest as they should.

Having grown up with parents who are designers and architects, you’ve been exposed to this field from a very young age. When did you first realize you wanted to become an architect?

Sahir: For the longest time, I didn’t want to be an architect because I saw how hard my parents worked and I wanted to explore other options, like archaeology or even acting. I considered being a bus conductor after seeing a movie. However, during 10th and 11th grade, I began to reflect on what I genuinely wanted to do. Architecture intrigued me because it combined my interests in both the arts and sciences.

My career counsellor suggested architecture or product design, so I spoke with my parents. They agreed but encouraged me to try it out first. I attended a summer program at the same college I later attended, and those six weeks were transformative. I learned that architecture was more about conceptualizing ideas and approaching projects differently than simply executing designs.The experience made me certain that architecture was the path I wanted to pursue. Each year in college deepened my interest, and it felt natural to follow this path, given my background. Seeing designs come to life and the process of construction reinforced my decision, making it clear that architecture was the right choice for me.

Given your international exposure & experience, what kind of additions would you like to bring to the firm?

Sahir:One of the key aspects I’m excited to introduce is enhancing how we present and experience architectural designs. Currently, we rely on technical drawings and 3Dmodels to convey our ideas. However, for clients who aren’t familiar with architectural jargon, it can be challenging to grasp the feeling of a space. To address this, I’m keen on integrating Virtual Reality (VR) into our process.

By using VR, clients can immerse themselves in a 3D model of their project before construction begins. This allows them to experience the space as if they were actually inside it—feeling the light, spatial relationships, and materials firsthand. For example, during a recent residential project, we used VR to let a client walk through their future home. They could navigate from the entrance to various rooms, experiencing how the space would function in real life. This approach not only helps clients understand the design better but also provides valuable feedback that we can incorporate before the physical build starts.

Regarding execution, effective project management and communication are crucial. Currently, we need to improve how stakeholders align on a unified platform. For this, I’m advocating for the adoption of Building Information Modeling (BIM). BIM integrates all project details into a single model, updating plans and models simultaneously as changes are made. This reduces miscommunication and ensures that all parties—structural engineers, plumbers, HVAC specialists—work from the same data. To make this work, we need all stakeholders to adopt BIM and communicate through centralized platforms. This way, when changes occur, everyone is updated in real-time, reducing errors and the need for on-site adjustments. Returning to work with Habitat Architects, I’m thrilled to build on the strong foundation established by my parents over the past 40 years. Their reputation and trust in the industry provide a unique opportunity to implement these advancements, enhancing both our design process and client satisfaction.