Reports suggest that the world has lost nearly 10 million hectare of forest each year due to deforestation, which is close to the size of Iceland. Going at this rate, researchers predict the world’s forests would disappear in the coming 100 to 200 days. With the aim to curb deforestation by providing an environmentally friendly and low-waste alternative, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have enabled the production of wood products with little waste by demonstrating the properties of lab-grown plant material. Here is a detailed report on SURFACES REPORTER (SR).

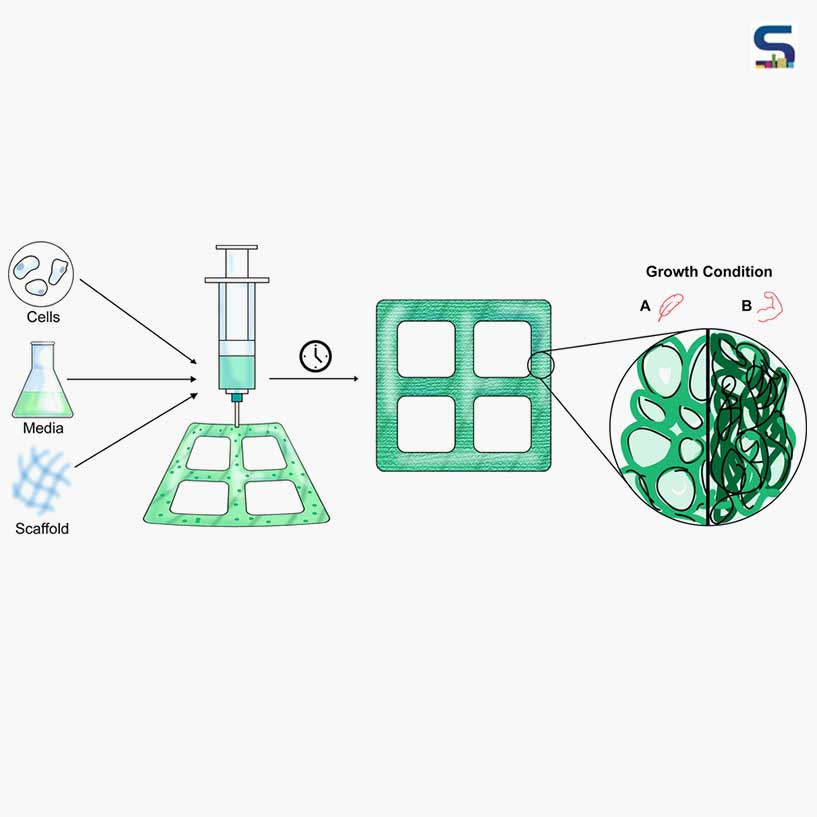

By adjusting certain chemicals that are used during the growth process, the MIT researchers inform that they can control the physical and mechanical properties of the resulting plant material such as its stiffness and density. This tunable technique aims at generating wood-like plant material in a lab that would help to grow wooden products like tables and chairs without the need to cut down trees. With the help of 3D bioprinting techniques, the researchers can enable this plant material to grow in varied shapes, sizes and forms which are not found in nature and cannot be produced by using conventional agricultural methods.

The team includes lead author Ashley Beckwith, Luis Fernando Velasquez-Garcia, principal scientist-Microsystems Technology Laboratories, MIT and Jeffrey Borenstein, a biomedical engineer and group leader at the Charles Stark Draper Laboratory. They have published their research in the journal Materials Today, while their research is funded, in part, by the Draper Scholars Program.

Artificial wood

According to Beckwith, who sees the potential of growing these 3D structures, this technique aims at eliminating any subtractive manufacturing, thereby reducing energy and scrap waste. Despite the research being at its early stage, it aids researchers to grow wood products with the exact features for any application.

The team started with isolating cells from the leaves of young Zinnia Elegans plants to grow plant materials in the lab. For two days, these cells had been cultured in liquid and then transferred to a gel-based medium that contained nutrients and two different hormones. The researchers adjusted the hormone level at this stage so as to tune the physical and mechanical properties of the plant cells that grow in that nutrient-rich broth.

Elaborating on this step, Beckwith draws a comparison with the human body. “You have hormones that determine how your cells develop and how certain traits emerge. In the same way, by changing the hormone concentrations in the nutrient broth, the plant cells respond differently. Just by manipulating these tiny chemical quantities, we can elicit pretty dramatic changes in terms of the physical outcomes,” Beckwith explains.

These growing plant cells act like stem cells. To extrude the cell culture gel solution into a specific structure in a petri dish, the researchers use a 3D printer and allow it to incubate in the dark for nearly three months. According to the team, the incubation period is faster than the time it takes for a tree to grow to maturity. Upon completion of the incubation period, the cell-based material is dehydrated.

The result

The team grew plant material with a storage modulus (stiffness) similar to that of some natural woods. They discovered that the lower hormone levels give in the plant materials. Open cells resulted in lower density while higher hormone levels added to the growth of the plant material with smaller and denser cell structures. The higher hormone levels also gave in the plant materials that were stiffer.

Through their research, they also highlighted the study of lignifications. Lignin is a polymer that is deposited in the cell walls of plants which makes it rigid and woody. Higher hormone levels were found in the growth medium due to more lignification, thereby enabling the plant material to appear more wood-like.

With the help of the 3D bioprinting process, the team demonstrated that the plant material can grow in any shape and size. Instead of opting for a mould, the team went ahead with the use of a customizable computer-aided design file that is connected to the 3D bioprinter. The bioprinter places the cell gel culture into a specific shape. Additionally, the team also demonstrated that the cells can survive and continue to grow for months after printing.

Photograph: The research team; Courtesy: MIT