The rhythmic crash of waves against the shore often brings a sense of peace but beneath this beauty lies a powerful natural force capable of causing significant damage to coastlines, infrastructure and marine ecosystems. Wave action, particularly during storms or high tides, can erode shorelines, threaten buildings and sea walls and compromise habitats. To mitigate such damage, wave-dissipating blocks are often installed. Traditionally made from concrete or cement, these blocks are designed to absorb and break the energy of incoming waves. While effective in protecting shorelines, these conventional materials come with notable drawbacks. Cement production is one of the leading contributors to global carbon emissions, and these artificial structures do little to support marine biodiversity.

In response to these challenges, two innovative design students from Taiwan, Chia-Ying Chiang and Shao-Yu Lin, have developed a more sustainable and ecologically sensitive alternative called the Ecotrapod. This project, which they describe as a new solution to wave dissipation, has earned them national recognition and awards in Taiwan. The Ecotrapod is a wave-dissipating structure that not only protects coastal areas but also nurtures marine life and dramatically reduces environmental harm. Know more about it on SURFACES REPORTER (SR).

The Ecotrapod is a wave-dissipating structure that not only protects coastal areas but also nurtures marine life and dramatically reduces environmental harm.

A Wave of Change

Unlike traditional wave breakers, which rely heavily on cement, the Ecotrapod is made using a material called Circular Slurry (C-slurry). This is a recycled composite material that the designers enhanced by mixing in discarded oyster shells, which is an abundant waste product in many coastal areas. This innovative blend results in a durable, marine-compatible substance that reduces or even eliminates the need for cement, thereby cutting carbon emissions by an impressive 30 per cent to 90 per cent.

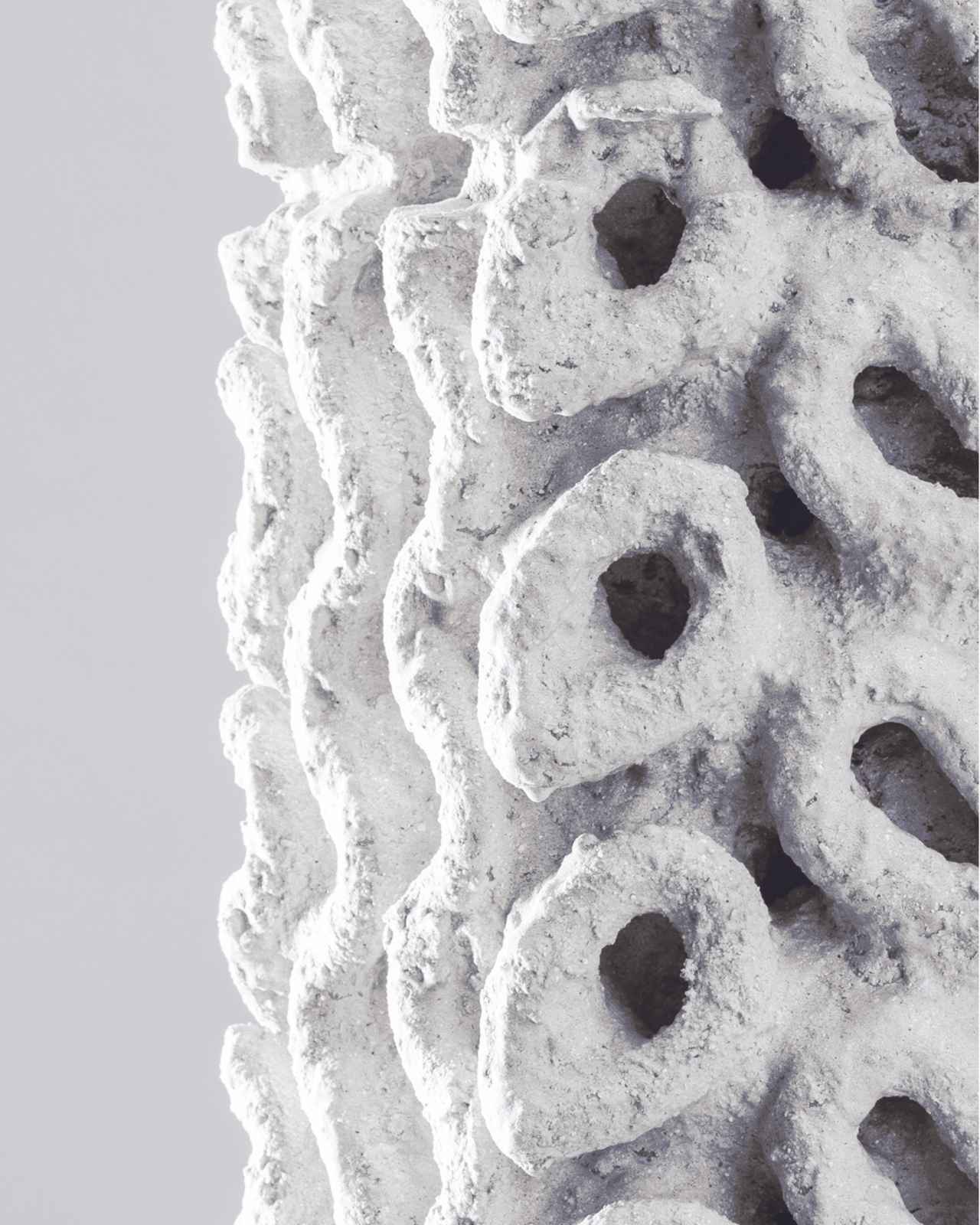

The design of the Ecotrapod goes beyond materials. Structurally, it adopts biomimetic principles by drawing inspiration from nature’s own engineering solutions. The blocks feature spiral, porous surfaces that maximize structural integrity while allowing the surrounding marine environment to thrive. These bio-porous surfaces include holes and crevices designed specifically to encourage the attachment of algae and provide shelter for small fish and shellfish. As a result, the blocks do not merely stand as static barriers to the ocean, rather they become living microhabitats that enhance biodiversity and promote a healthier marine ecosystem.

This is a recycled composite material that the designers enhanced by mixing in discarded oyster shells, which is an abundant waste product in many coastal areas.

Circular Sea Solution

This dual functionality of protection and regeneration is central to Chiang and Lin’s vision. They designed the Ecotrapod not just to solve an environmental problem but to engage visitors with the beauty and complexity of ocean life. The blocks, with their natural shapes and integrated ecology, appear as extensions of the sea rather than intrusive barriers. Coastal visitors might observe fish darting through them or algae gently swaying in the current, turning a functional structure into an educational and immersive experience.

To bring their idea to life, the designers collaborated with organizations including C-Cube, Lotos and Everplast. Through these partnerships, they were able to advance their vision from concept to reality, guided by their shared love of the ocean and commitment to creating sustainable ecological solutions. Furthermore, the use of 3D printing technology in the construction process not only enables intricate, functional designs but also minimizes material waste. This precision manufacturing process further reinforces the sustainability of the project.

In line with their circular design philosophy, the Ecotrapods are fully recyclable.

In line with their circular design philosophy, the Ecotrapods are fully recyclable. Once a unit has reached the end of its useful life, it can be crushed and repurposed to create new blocks, thereby closing the loop in a continuous cycle of use, reuse, and regeneration.

Image credit: Chia-Ying Chiang and Shao-Yu Lin