Architecture practice Iksoi Studio recently transformed a disused industrial structure in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, into its new headquarters. Named Mana, the project represents not just a physical retrofit but also a deeply personal journey, as it draws on memory, family legacy and a sense of belonging. Sibling architects Dhawal and Mansi Mistry, both involved with Iksoi Studio at the time, spearheaded the design and weaved together the site’s industrial past with a new architectural identity. Know how the architects have made an adaptive reuse of a factory on SURFACES REPORTER (SR).

Named Mana, the project represents not just a physical retrofit but also a deeply personal journey, as it draws on memory, family legacy and a sense of belonging.

Nostalgic design

The site itself carries significant history. When it was an operational unit run by the Mistry family, it was originally used by their father to manufacture spare parts for power looms. After being active for years, the factory was eventually shut down in 2009, leaving behind its buildings and tall enclosing walls. Instead of erasing this past, the architects chose to reinterpret it. They adapted the compound into a 186sqm workspace that could house both the architectural studio and its supporting functions.

They adapted the compound into a 186sqm workspace that could house both the architectural studio and its supporting functions.

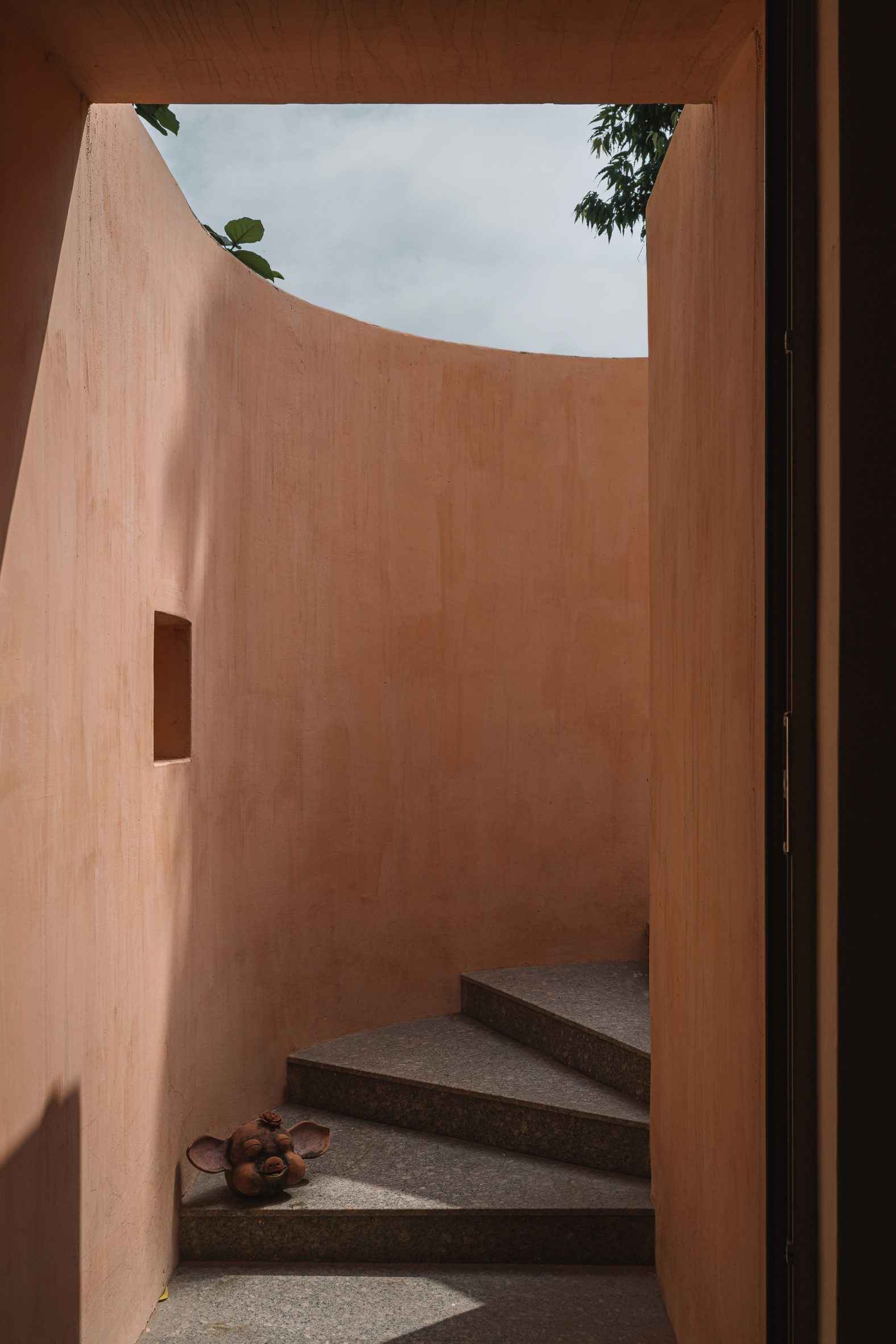

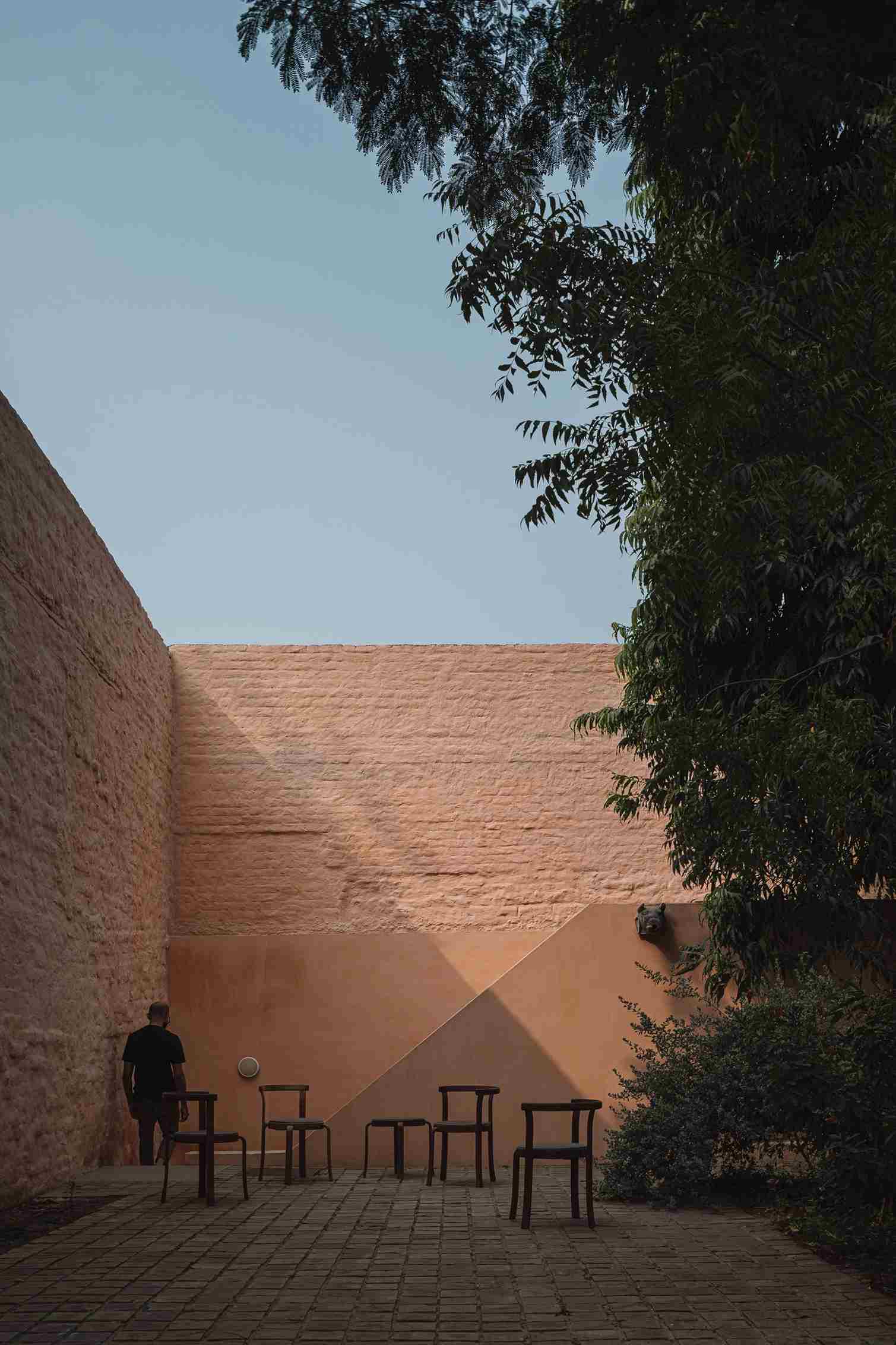

The campus comprises two primary blocks, a smaller structure along the boundary wall and a larger central volume. In the retrofit, the smaller block has been reimagined as the architecture studio, while the larger one, which once contained heavy machinery, now serves as a warehouse. Although the basic layout was preserved, the architects altered the ground levels of the central courtyard. By raising the courtyard floor, they created the unexpected visual effect of the built volumes appearing partially submerged into the earth. This subtle design move also transformed old doorways into windows, allowing the new workspace to retain a tangible connection to the former factory.

In the retrofit, the smaller block has been reimagined as the architecture studio, while the larger one, which once contained heavy machinery, now serves as a warehouse.

The name Mana is symbolic. It pays homage to the family’s pet dog, who is buried under one of the site’s trees, embedding another layer of memory and sentiment into the project. This approach reflects the larger design philosophy that guided the work, thus embracing familiarity, nostalgia and emotional resonance as core design inspirations.

Blending memory and materials

Materiality and colour played a pivotal role in redefining the site. The original grey factory walls, weathered and marked by years of industrial use, were carefully lime-plastered and finished in muted shades of pink. This choice was deliberate as the architects wanted to preserve the structural essence but contrast it with warmth and softness. A mixture of cement and lime was used to achieve this distinctive finish, which set the tone for the new identity of the campus.

This subtle design move also transformed old doorways into windows, allowing the new workspace to retain a tangible connection to the former factory.

To enhance spatial experience, the architects also introduced a rhythm of arches. These interventions broke down the narrow, elongated proportions of one of the blocks, creating a sequence of defined work cubicles that feel both intimate and functional. At the quiet end of one corridor, the principal architect’s office was placed to overlook a concealed courtyard, allowing for a calm and contemplative workspace.

The original grey factory walls, weathered and marked by years of industrial use, were carefully lime-plastered and finished in muted shades of pink.

Further layers of history and locality were embedded through the choice of furnishings and details. Original mid-century Danish chairs from Gujarat’s famous ship-breaking yard at Alang were sourced grounding the interiors in a sense of place and heritage. Small sculptural elements such as playful gargoyles were scattered around the site, adding a whimsical character that complemented the otherwise restrained architecture.

Original mid-century Danish chairs from Gujarat’s famous ship-breaking yard at Alang were sourced grounding the interiors in a sense of place and heritage.

The material palette also reflected the site’s industrial context. Granite was used indoors, while cobbled limestone paved the outdoor spaces, materials that were not only appropriate but also sourced conveniently from the adjacent workshop that continued to process them. The interplay of stone, lime and plaster tied the project back to its local roots.

Image credit: Ishita Sitwala